The Stabilization Facility for Libya (SFL) project aims to bridge Libya’s period of transition from an initial humanitarian relief towards mid- and long-term structural and sector-specific support after the 2011 revolution by strengthening national unity and reinforcing state authorities. The project has been implemented by UNDP since 2016 with activities under three main components (outputs): i) restorage of basic services and light infrastructure; ii) immediate capacity support for municipalities and local partners; and iii) local peace structures and conflict management capacity. Since 2020, UNITAR’s Peacekeeping Training Programme (PTP) is supporting UNDP in the delivery of activities under Output 3 on “Local Peace Structures and Conflict Management Capacity”.

UNITAR’s support to the project implementation has been structured in two components: training and coaching and mentoring. The training workshops are aimed at enhancing the knowledge and skills of local Libyan Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) in the technical areas of project cycle management as well as conflict management, including the analysis, mapping, and monitoring of conflicts, and techniques to support the transformation of conflict through dialogue and other transformation strategies. Moreover, pre-selected CSOs have the opportunity to apply for UNDP low-value grants, the first of which was aimed to develop and implement a conflict analysis focused on a specific conflict present in their local context. In such framework, UNITAR has supported the selected CSOs to develop a Conflict Analysis Report for their application process through one-to-one mentoring and coaching sessions. Gender has been mainstreamed throughout all the project activities.

During 2020-2021, eight online workshops were delivered by UNITAR, including one Training of Trainers (ToT). Three additional trainings have been delivered in 2022 to continue strengthening capacities on the topics mentioned above. Furthermore, a face-to-face event was organized in Tunis in March 2022 as a stocktaking exercise to discuss the status of implementation of the first low value grant and as opportunity to allow the Libyan CSOs to further strengthen their connections to one another. Box 1 lists the online training sessions delivered during 2020-2022.

This Impact Story collects experiences of how programme participants have applied or transferred knowledge and skills from the capacity development activities implemented during 2020-2021 (training 1 to 8) to their organizations. It also provides a summary of the conflict analysis reports developed by the CSOs.

Participants’ feedback was collected through an online survey deployed in two phases: in October 2021 for those who attended the first three trainings and in June 2022 for the subsequent trainings. The surveys were available in Arabic and English. Additionally, four video testimonials of participants joining the face-to-face event in Tunis in March 2022 were reviewed, to better understand any change that may have occurred in their workplace derived from the training sessions.(1)

Twenty-five responses were received in total from the two surveys, while only six participants responded to the two surveys. Therefore, there is a difference in the number of responses per question. The number of responses was considered for the data analysis and reported in this Impact Story, accordingly. Not all respondents participated in all training sessions with the number of sessions attended ranging from two to eight (all sessions). The training sessions with more respondents are conflict analysis and stakeholder mapping, project implementation and project technical reporting, and the ToT on conflict reduction strategy design.

Further respondents’ characteristics and application of knowledge from the training are reported in the below section.

(1) PPME usually uses interviews as a data collection tool for triangulating information collected through surveys. However, this Impact Story uses testimonials collected from programme management during the face-to-face event in Tunis. Still, the overall methodology for Impact Stories was followed.

Application of knowledge and skills from the training sessions

The programme participants have large professional experience in their organizations’ field of interest. Nineteen respondents (76 per cent) are in senior or management positions in their organizations. Although the project targets local CSOs, three out of twenty-five survey respondents indicated working in national government organizations. Regardless of their position or organizational affiliation, all respondents considered that the training topics were important for their job performance.

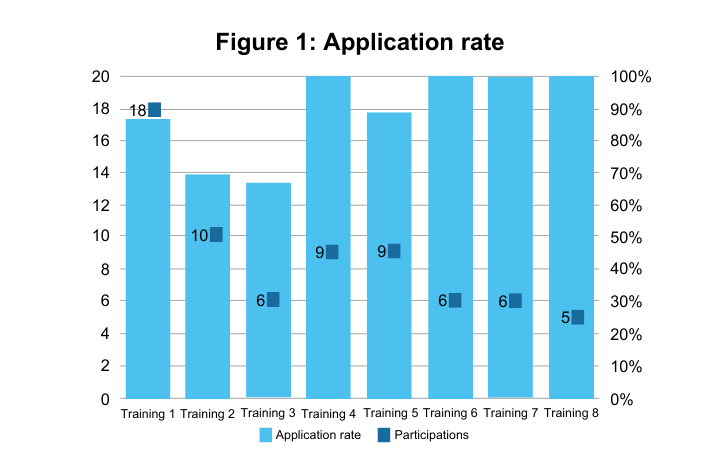

Overall, the application rate of knowledge and skills from the training is high (above 80 per cent) for all training sessions, except trainings 2 and 3. The application rate and participation of survey respondents(2) by training session is presented in Figure 1. It is noteworthy that respondents have been able to fully apply knowledge and skills from four out of eight training sessions, i.e., the application rate of four of the training sessions is 100 per cent. On average, respondents attributed applying new knowledge and skills to their jobs to the UNITAR training, in at least 70 per cent (or seven points).

After two years of delivering the training component, changes in application and transfer of knowledge and skills and in the project teams’ dynamics were documented. Application of knowledge and skills from the training was found in the areas of project design and implementation, conflict analysis and research, budget preparation, and communication skills. Internal and external training or informal transfer of knowledge to colleagues and one example and changes in work dynamics (e.g., how to handle internal conflict) was indicated as changes derived from the UNITAR training component by survey respondents. Specific examples of application are shown in Box 2. Particularly, for the ToT session (training 5), five respondents (55 per cent) have already conducted multiplications of the training sessions in their organizations. The main reasons hindering multiplication for the remaining four are lack of funding or support to conduct a training and time constraints (too busy to train).

Box 3 showcases Najet’s experience in applying knowledge and skills from the training components of the project.

(2) The number of participants per training session should be read carefully, as we have received some partial responses. Then, lower number of respondents is dependent on survey completion.

Changes in participants’ organizations related to gender include the inclusion of gender in monitoring tools (monitoring of activities including gender considerations), amendments of policies to make them more gender-sensitive, strengthening of existing gender approach in the organization culture, targeting women as beneficiaries (e.g., verifying gender ration of beneficiaries in their programming), and ensuring equal female-male ratio during the elaboration of the conflict analysis report.

Further experiences of incorporating gender analysis and considerations in the conflict analysis reports have been mapped among the partner organizations either as a central topic of the analysis or in the methodologies used, e.g., in the data collection phase. Specific examples are listed below:

- “Athar Organization for Development and Empowerment” focused on assessing the influence and engagement of women on peacebuilding efforts in Sabha city and the impact of the tribal local conflict on their current situation. To that end, Athar specifically selected and trained women researchers to carry out the fieldwork (focus groups discussions and semi-structured interviews) to have more access to and openness from women respondents and include their opinions in the conflict analysis. “Solidarity for Women Support and Empowerment” organization also focused their conflict analysis report on women.

- “Mizan Development Organization” and “Afaq Al-Hiwar Foundation” conflict analysis reports organized a separate focus group for women during the data collection phase. Similarly, the report from “Libya Foundation for Sustainable Development” organization held one focus group specifically dedicated to identifying the gender dimension in conflict analysis and its impact on conflict dynamics. Four other organizations also ensured balanced gender ratio of focus groups’ participants and closely monitor the survey respondent’s gender to have representation of women in the survey responses.

- Similarly, the conflict analysis project of “Solidarity for Women Support and Empowerment” focused on understanding the women's point of view, priorities, and concerns; consequently, the participants in the focus groups and the survey were all women from different parties to the conflict.

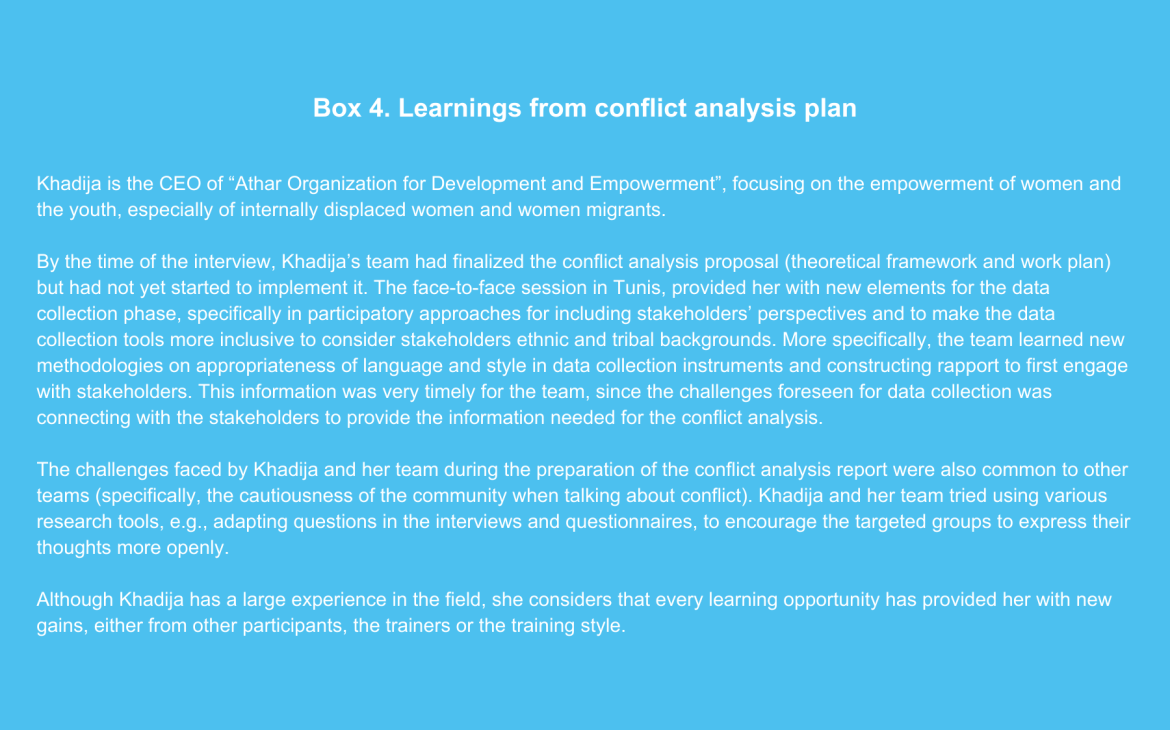

Although the application rate from training was high, there were some factors that have slowed this process. Time and funds available were the main factors that hindered the application of knowledge. On the other hand, factors that enabled the application of knowledge were support from UNITAR resource persons, supervisors at work and project team; training design and methodologies, including the contextualization to the Libyan context; opportunity to apply knowledge and skills, and sufficient knowledge to be applied. Notably, since most respondents were in senior positions and had previous experience, they probably had some opportunity to apply the learning from the training.

While most respondents recognize contextualization of knowledge as a positive factor, they recommended more interactive sessions (not necessarily in-person) with conflict case studies from Libya and presentation of the work of other participating organizations. The Moodle platform was well received by respondents, but some of them reported having connectivity problems and power cuts which affected the flow of the online sessions. A desire for face-to-face activities persists among participants.

Some suggestions related to the training format are increasing time of trainings and selecting more appropriate training hours. One recommendation gathered in the first survey was the delivery of follow up sessions. Consequently, three additional training sessions have been conducted in 2022 as learning reinforcement. Six of the respondents have already participated in these new training and rated them as very or fully effective to reinforce or complement the knowledge and skills acquired previously in the eight training sessions.

Coaching and mentoring: conflict analysis reports

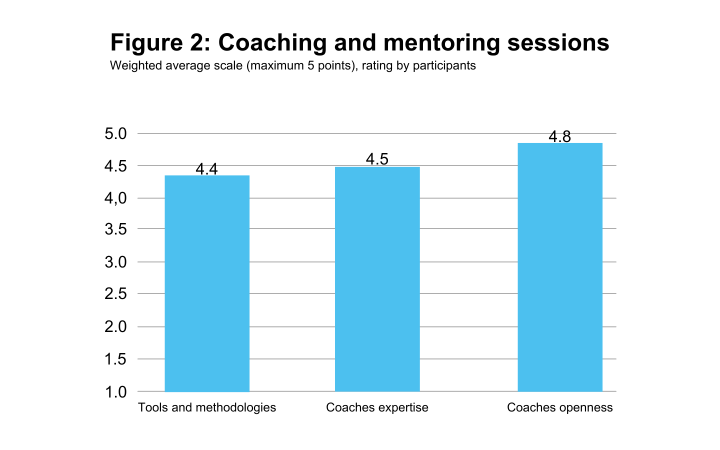

Fifty-six per cent of respondents (14) received one-to-one coaching and mentoring from UNITAR on conflict analysis or stakeholder mapping. Almost all of them applied to the UNDP first low-value-grant opportunity (12 respondents).(3)

The coaching sessions were key hands-on experience to translate the technical knowledge from the training sessions to the participants’ work. The project teams highlighted that the coaching sessions brought new information and complemented the training sessions. The sessions provided additional information on project development and on the proposed issue of conflict analysis as well as how to write meaningful proposals and financial reports. The new information from the sessions was also incorporated into the development and design of other projects in the organization. The coaching sessions also represented a good opportunity to obtain guidance on priority needs of the participants’ organizations and to review mistakes in their proposals. This additional knowledge check was important for consolidating respondents’ understanding and to address challenges encountered during the proposal drafting process.

One of the respondents indicated gains from their organization at increasing the networks with local authorities and communities on which the project proposal was focused, which will probably be continued after the training programme and project proposal development with UNDP.

Conflict analysis reports’ themes are diverse, ranging from analysis of women in conflict, IDPs, land conflict, among others. The full list is presented in Annex 1.

During the development of the conflict analysis reports, application to and reception of the funds were the major challenge faced by teams. Technical challenges, e.g., data collection, were also encountered by project teams. The coaching and mentoring component was key to overcome these technical challenges. Box 4 exemplifies some technical challenges encountered during project planning.

(3) The total number of participant organizations receiving mentoring and coaching was 20, of which 14 were pre-selected for the grant (one withdrew from the process). This section is based on survey responses (figures in the text) and additional information about the conflict analysis reports from internal project monitoring data shared by the project team.

Conclusion

Learnings from UNITAR training, as part of output 3 of the project, have been incorporated in the work functions of some participant CSOs. The application rate is high among survey respondents. Application of knowledge and skills from the training sessions is diverse. Most of the application is linked to the conflict analysis plan being developed by project teams, but there are also some examples of changes in work performance and internal organizational dynamics. Internal knowledge transfers to other colleagues (formally or informally) have occurred in many participants CSOs. While not all respondents participating in the ToT session have been able to carry out multiplications, some of them have applied some skills from the session to their daily jobs.

The coaching and mentoring sessions provided a good opportunity not only to refine the conflict analysis plans for obtaining the micro-grants but to acquire new knowledge and reinforce the existing knowledge. Coaching methodologies and expertise from coaches was well received by participants.

Although not systematically found in all participant organizations, gender considerations in project management were incorporated by some participants in their project management tasks, such as monitoring tools and gender-balanced beneficiaries.

The conflict analysis plans are currently in different stages and only a few are being implemented, mostly because project teams are still applying for the micro-grants. Therefore, this Impact Story did not collect any evidence on any organizational changes related to the implementation of the conflict analysis plans. It is therefore recommended to follow up on any additional changes that may occur in the organizations after fully implementing the plans.

General recommendations from participants for future training are to make sessions more interactive and to include more examples or case studies from the Libyan contexts, e.g., from other Libyan organizations.

Annex I. Conflict analysis reports

- Conflict in Ubari Town between Tawareq and Tebu tribe: ensuring that infrastructure projects are conflict sensitive and sustainable and that Ubari’s social fabric and peace-oriented institutions are strengthened and enhanced.

- Conflict in Murzuq between Arabs Tabu and its effects on the rest of the municipalities of the Fezzan region: better understanding of the parties in the conflict, its gender dimension, and the motivators that contributed to its exacerbation and complexity, as well as the factors that may help solve it or mitigate it.

- Dispute between Elmaadani and Elbarki families over land ownership in Benghazi: to shed light on the analysis of the conflict between the two tribes and seeking to understand the root causes of the conflict, its parties, as well as its dynamics at the local level.

- Women’s exclusion from local peace processes in Sabha and impact of the tribal conflict on their situation: understanding the roots that affect women’s role and participation in mitigating conflict, in addition to understanding the available and possible intervention strategies to design projects that contribute to reducing conflict through direct women’s intervention.

- Tension between the IDPs from Tawergha and hosting community in Benghazi: understanding the realities of the two parties and the dynamics of the conflict and link it to the dividers and connectors within the context.

- Conflict between Janzour and Al Mayah armed groups, near Tripoli: understanding deeper the conflict, its root causes, parties involved, dynamics, time curve, and how these dimensions affect or are affected by other conflicts; and highlighting possible entry points for potential interventions to address conflict at the local level.

- Causes of conflict and tension holding the return of Tawergha IDPs to their town: identifying the root causes of the conflict - including the needs and concerns of women -, the conflict dynamics, and the dividers and connectors.

- Conflict between CSOs and local authorities in Ghat municipality: analysing and understanding the nature of the conflict to find a consensual ground for action for partnership and joint work.

- Dispute over Safsafa plots project in south of Benghazi: analysing the conflict from the perspective of government agencies and university professors.

- Analysis of the tension between the IDPs from the East and hosting community in Misrata: identifying the root causes of the conflict, conflict dynamics, time curve and how these dimensions affect or are affected by other conflicts, as well as the gender dimension in conflict analysis.

- Dispute between farmers and local authorities over water in Sirte: deliver a deeper analysis of the root causes of the water shortage and provide potential solutions to the problem as collected form the parties to the conflict.

- Tension between the families of missing persons from Tawergha and local authorities and committees: analysing the root causes of the conflict between the families of missing persons, the Committee - Misrata Peace treaty, and the local authorities of Tawergha and Misrata.