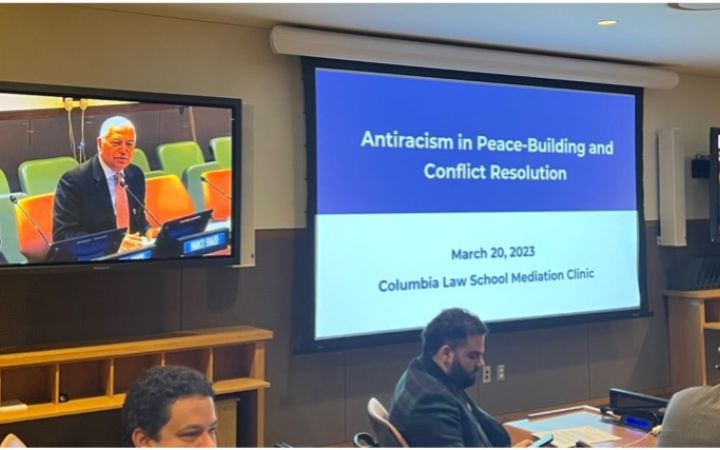

20 March 2023, New York, USA – The United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR), New York Office and its trusted partner, Columbia Law School hosted their “Antiracism in Peace-Building and Conflict Resolution” workshop on Monday, 20 March 2023. The workshop was the first of three sessions of the Spring 2023 Columbia Law School Mediation Clinic training series, it was developed in a hybrid manner and attended by more than 120 participants.

The concept of anti-racism and peacebuilding is culturally specific, as different countries and places have unique engagement with race, racism, and conflict. This presentation aimed to embrace these differences and create a rich conversation that encourages participation from everyone. The programme was led by Brenton Brown, Kevin Cryan, Skylee Sasha Youssef, Sonia Helen Pascal, and Rebecca Price in place of Alex Carter, who typically runs Columbia Law School's mediation programmes but is currently on sabbatical.

Mr Marco A. Suazo, head of the office of the NYO opened the session by introducing the series to the participants and the lead trainer professor Price, who first started by introducing the objectives of the workshop, namely identifying how race and racial bias manifest in conflict resolution, how a leader should navigate them to provide access to justice for all, and finally, discussing the best-practices when it comes to identity-based bias. To this end, the attendees engaged in an icebreaker which encouraged them to reflect on their past experiences related to identity-based bias and to share them with their peers. This enabled them to get to know each other and also unlock their prior knowledge. As communication is inherent to any harmonious relationship, It was emphasized that it is important to clarify the problem verbally and to express one's feelings to avoid a recurrence.

The speakers then went on to define the concept of racism as the prejudice, discrimination or antagonism by a party against another one on the basis of their membership in an ethnic or racial group. During their explanation, they described three levels of racial awareness.

Diversity awareness acknowledges and respects differences but does not address institutional and systemic racism or social dynamics. Cultural competence, in turn, involves cross-cultural learning but creates and maintains a sense of otherness. Ultimately, there is antiracism, the active process of identifying and eliminating racism by changing systems, organizations, policies and practices. The speakers insisted that the opposite of racism is not “non-racist” but “antiracist”. According to them, the role of an anti-racist is to understand that inequality exists on the systemic level, evaluate it from a broad societal perspective and address how existing policies underserve people of colour. Therefore, in Peace-building and Conflict Resolution, antiracism enables a work environment with diverse cultures in which people can identify and confront issues to foster inclusivity and promote access to justice. One student intervened saying that the goal of anti-racism is not only about power being re-distributed but for people to recognize we are humans with the rights that require dignity and rights to live without fear of being judged.

Later on, the speakers tackled the way racism shows up in conflict resolution. The first instance is an overt bias which can take the form of direct prejudice, exemplified by the use of racial slurs or stereotypes. The second one is institutional scepticism, meaning that racial, ethnic or religious groups may lack trust in certain institutions. These structural doubts rooted in past mistreatment may hinder peace-building and conflict resolution. In addition, racism or racial dynamics can constrain communication between parties, by creating a sense of isolation among minorities, silencing and sidelining them, or oversimplifying issues. Implicit bias is also an important part of conflict resolution as people cannot control social perceptions and judgements which can affect interactions. A discussion question was then issued, aiming at exploring manifestations of racism in the attendees’ community, country or culture.

The last topic before the break was colour blindness vs. colour consciousness. When neglecting to consider race-based differences we risk undermining the fostering of an inclusive environment by ignoring manifestations of discrimination, whereas consciousness better addresses inequity by building sustained commitment in cross-sector spaces.

Then, the speakers started discussing leadership tools for resisting racism in conflict resolution. First, a leader should ensure procedural fairness through awareness, and inclusive participation among other things. They should also make sure to regulate their own and other party biases to disrupt racist processes. Acknowledgement and stroking are another important part of antiracist leadership: pointing out progress and praising it. The concepts of reframing, summarizing and clarifying are important for effective communication and mutual understanding. Naming the issue to help the parties, and confront it as part of the process. The speaker also pointed out the importance of one-on-one conversations to understand the interests behind the parties’ positions. This type of individualized conversation includes many benefits such as gathering information and de-escalating. However, it is important to know when and how to walk away or break the conversation.

The final interactive segment of the session engaged the attendees in two hypothetical scenarios in which they discussed how to facilitate the dialogue between two parties. The first scenario presents a case of direct assertions of racial bias and discrimination between a junior employee and her supervisor. The second one is about representation: a country chooses a lighter-skinned representative over a dark-skinned one even though the latter has more legitimacy. In both hypothetical situations, the participants had to identify potential biases and apply the tools seen during this workshop.