In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Lavinia Taumoepeau-Latu left Tonga to join her children in the US and to care for a sick sister. She has since been waiting for Tonga’s borders to reopen so she can continue her work in Tonga.

When a large part of Texas lost power in February 2021 due to three severe winter storms, it made Lavinia reflect.

Big countries have the opportunity and the resources to prepare for things like this. But it’s not on their mind,

she says. Tonga, on the other hand, may not have such resources, but “they’re always preparing, they’re always thinking about disaster.”

Tonga and natural disasters

Small island developing states like Tonga face dire consequences of the climate crisis. The country consists of 171 islands – of which 36 are inhabited – spread over an area roughly the size of Japan. Ranked second highest in the world for disaster risk (2020 World Risk Index), the low-lying country is prone to annual cyclones, storm surges and flooding – made worse with rising sea levels – and droughts induced by El Niño.

Tonga has seen an increase in the number and intensity of cyclones in the last 30 years. The 2018 Cyclone Gita, the largest tropical cyclone on record to hit Tonga, is estimated to have caused approximately US$164.1 million of economic damage, nearly 38 per cent of the country’s nominal gross domestic product.

Lying near the meeting place of two tectonic plates, Tonga is also susceptible to earthquakes and tsunamis, with more than 200 earthquakes occurring near the country each year. The World Bank estimated in 2015 that earthquakes and tropical cyclones would cost Tonga US$15.8 million per event per year, on average, over the next 50 years.

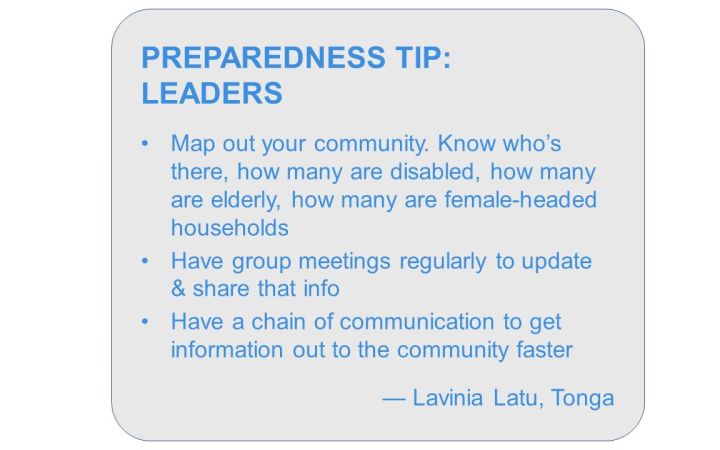

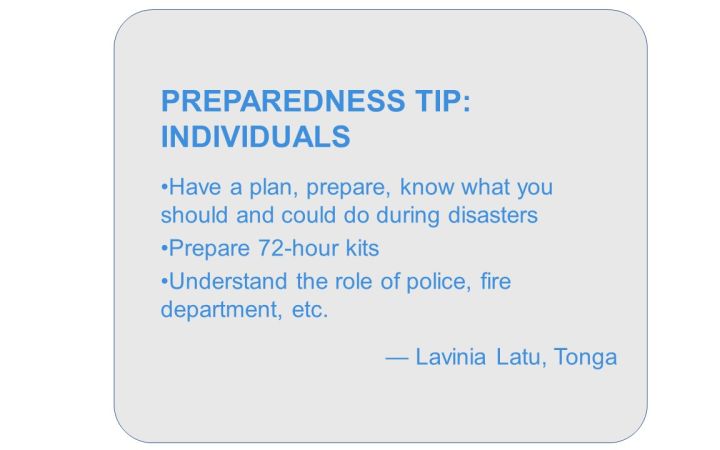

Given the certainty of natural disasters, the small country has no choice but to be prepared. But no one actor can prepare everything, especially in a remote country with limited resources. This is why Lavinia believes it’s essential to bring community-level organizations and national government together in a coordinated effort.

Coordinating the disaster response: The cluster system

Lavinia grew up in the US, but her ancestral ties are in Tonga and she identifies as ethnically Tongan. In 2018, she moved to Tonga to join the Ministry of Internal Affairs as the safety and protection cluster coordinator.

Under the cluster approach for disaster response, national government agencies – led by a specific ministry – and civil-society organizations coordinate in key areas such as logistics, health, and food security. The system was initiated in the United Nations in 2006; Tonga adopted the approach in the aftermath of the 2014 Cyclone Ian.

There are about 10 different ministries [in Tonga], and every single ministry has a cluster that’s assigned to them. Safety and protection is within the Ministry of Internal Affairs, [whose] divisions include women’s affairs, youth, sports, local government, employment, corporate services,

says Lavinia. “One of the clusters or ministries will take the lead, depending on the disaster.”

While it is still in its early stages of development, Lavinia believes the cluster system has the potential to help key actors in Tonga coordinate well in emergencies.

Clarifying the roles and responsibilities: Standard operating procedures

In 2018, Lavinia took part in the UNITAR Tsunami-based Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) programme. The programme, supported by the Government of Japan, trains female professionals from small island developing states on leadership in disaster risk reduction. Nearly 200 women from the Pacific and Indian Ocean countries have been trained to date and are using what they learned to help their country better prepare for and manage disasters.

Through the UNITAR training, Lavinia learned of the importance of having standard procedures in place. “That was one of the things that I knew we really needed to focus on.”

Upon returning to Tonga, Lavinia worked with UN Women to develop standard operating procedures, terms of reference, and a code of conduct for the safety and protection cluster. These guidelines lay out the roles and responsibilities and reporting lines for an emergency situation. It clearly describes how, at the village level, the town officers are to gather information on the ground and report to the district officer; and the district officers are to report to the National Emergency Management Office (NEMO), which is responsible for emergency management in Tonga.

“It is a document to help guide the proper management of the cluster,” says Lavinia.

I think we are the first or maybe second cluster [in Tonga] that has gotten their standard operating procedures together.

In 2020, Lavinia was asked by the director of NEMO to share the standard operating procedures, terms of reference, and code of conduct so that they may be used as examples for other clusters.

Addressing the most vulnerable

Lavinia made sure the guidelines addressed how to prioritize the most vulnerable in the villages, such as single women and widows (one assessment, for example, found increased incidence of sexually transmitted infections among women following a disaster), and people with disabilities. The guidelines clearly state how to get supplies and support to those who need them the most and, where available, to refer them to further services.

Households headed by single women were particularly vulnerable, especially in the remotest areas. “One organization [was trying to] get water tanks out to female-headed households on an outer island affected by Cyclone Gita,” says Lavinia.

Some of these homes were in such rural areas. I could not imagine how [the organization] even found these women’s houses, let alone what [the women] were doing for water, because water is really an issue.

As recommended in the UNITAR training, the guidelines are grounded in the law – the 2007 Emergency Management Act – which gives them authority and enforcement power or the “teeth” to further protect the vulnerable from abuse. For example, individuals must sign the code of conduct before engaging in humanitarian activities in Tonga. If they do not adhere to the rules and the code, there could be legal consequences.

Building the community–government relationship

While serving the Tongan government, Lavinia – who comes from a grassroots work background – enjoyed working with the cluster’s many local civil-society organizations (CSOs). She could see, however, the disconnect between the national government and the grassroots CSOs.

Lavinia would attend the higher-level National Emergency Management Committee meetings and her reports of what she heard from the CSOs were always appreciated. She noted that the central decision-makers often lacked grassroots information and hence, national disaster preparedness and management efforts often focused on building and repairing infrastructure, for example, whereas communities could use other kinds of support.

“If [the government doesn’t] know what’s going on, then they think that everybody’s just okay,” says Lavinia. “So it’s important that there is a relationship between the government and the community – to build and establish that relationship – so they’re able to get the [assistance] out to the people.”

To pursue her vision after leaving her government position, Lavinia set up a non-governmental organization called Mo‘ui Manatu Kiho Tupu‘anga. Activities are on hold as Lavinia awaits the COVID-19 pandemic to simmer down and the Tongan borders to reopen. The organization will be developing training materials and focusing on coordinating community leadership and government for disaster management.

There’s beauty in trying to build and cultivate these relationships, and especially because [it’s a] disaster [we have to say], ‘everybody put your feelings aside, let’s just go try and work together and make good things happen.'

About UNITAR

UNITAR Division for Prosperity with the support of the Government of Japan helps women leaders from small island states strategize better to reduce disaster risks in their countries and communities.

The Pacific small island developing states have long been important partners to Japan, and the Government of Japan will be hosting the 9th Pacific Islands Leaders Meeting on 2 July 2021, where Pacific heads of state will discuss partnerships and common challenges.